FOREST CHOROGRAPHY

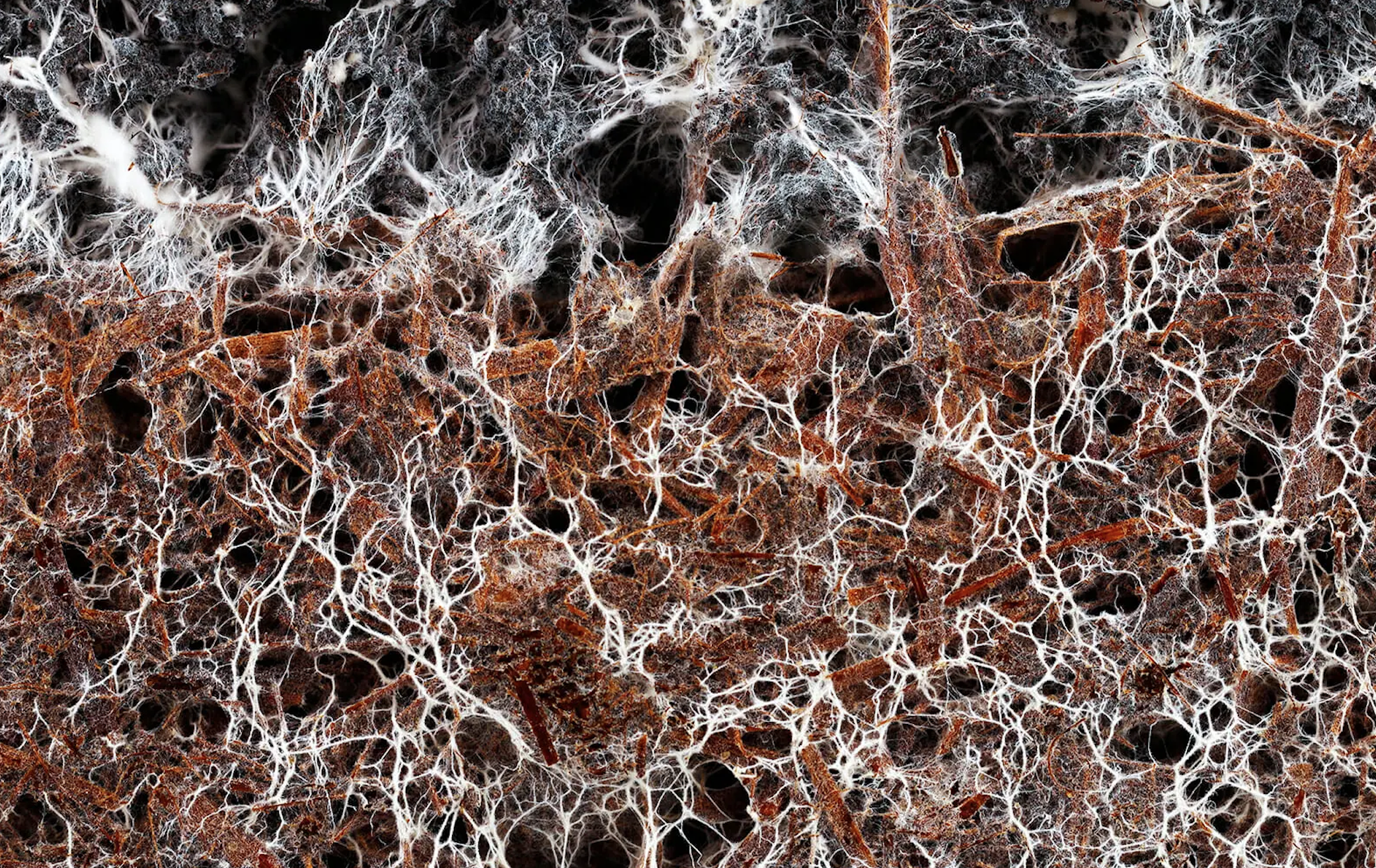

Mycorrhizae / MakroBetz/Shutterstock.com

We need more nuanced narratives for timber

“…the narrative that building with timber is automatically environmentally positive because timber stores carbon dangerously simplifies the host of ethical choices that arise in material specification. By pinning the narrative of timber’s sustainability to carbon, architects risk transforming forests-as-ecosystems into forests-as-plantations.”

— Laila Seewang, “Narratives of Sequestration”, E-Flux Architecture, Accumulation, December 2023

Architectural and urban “narratives of sequestration” promote timber building as a solution to multiple crises as once (i.e. the need for housing, and the need to reduce carbon emissions), but these stories originate in an extractivist and technocratic understanding of wood as resource, separated conceptually from the forests from which this once-living material originates. As calls for the regional sourcing of regenerative building materials grow louder, the reality of the deep existing entanglements between forests and humans is pushed aside in favor of simplistic carbon calculations (a carbon-based urban imaginary) that de-politicize the deeply ideological nature of current debates about ecology and technology.

As infrastructural/technological landscapes and extractive managerial surfaces, the patchy forested territories of central Europe are sites that manifest political and economic ideology; as multidimensional, multispecies ecosystems, their real complexities often confound our attempts to establish and maintain control. In the states of former East Germany, forests currently cover around 37% of the land and betray the intertwined legacies of Prussian scientific forest management, Soviet-era militarized agricultural collectivization and plantation forestry, and modern-day climate stresses as well as the economic forces of global capitalism. The dominance of industrialized monocultures is only one legacy of the disastrous extractivist visions of the GDR, which produced extreme pollution and brought ecosystems to the brink of collapse; even today, a full 71% percent of the trees in the state of Brandenburg are single species, the Pinus sylvestris or Scots pine, which was planted in huge plantations by the GDR government after the ravages of WWII. 40% of the forested area still consists of pine plantations.

When we focus solely on carbon flows, ecology enters the realm of the “post-political”, as deeper questions about the core mechanisms that drive climate change, in particular concerning market forces within the conditions of global capitalism, are not asked. In his invocation of the “managerial surface”, John May notes that when the environment becomes nothing more than a problem to be solved, management mechanisms are everywhere at once, extending even to places that seem wild: the layering of an idealized image of “nature” over a subsurface of exacting control mechanisms is in fact a hallmark of modern environmental management. These techno-managerial landscapes — shot through with physical, administrative, financial or regulatory infrastructures — reflect a deep desire for “legibility” and control. Since power is concentrated in the hands of those who can create legible representations of their ideas through an alignment with dominant scientific discourse, moreover, other ways of knowing or being in nature — including diverse nonhuman entanglements, or ideologically/politically inconvenient perspectives — are flattened into what eco-philosopher Timothy Morton might refer to as easily digestible “Easy Think Natures”.

A chorography is a term used historically to describe regional atlases that combined local topographical description with historical knowledge and stories. The chorographic approach qualitatively maps characteristics of place through an examination of its constituent parts. Building on the rich literature of critical cartography and the work of allied researchers and artists, the digital/analog “Chorographic Atlas of Brandenburg” will take advantage of digital media to host indexed and networked “narrative windows” into these forests, as a spatially grounded methodology for critical representation that creates de-centered “ontological openings” to weave a path through complexity without creating a totalizing frame. In a nod to artist Ursula Biemann’s use of the word in her own work, each window can be thought of as an individual “file”.

These files will weave photographic, textual, filmic, critical-cartographic and other forms of representation (of: fungal networks, sawmills, processes of evapotranspiration, soils…) into an Atlas that tells multiple, ontologically de-centered and interwoven stories. As the product of an interweaving of many voices, the Atlas will enable critique of technocratic and de-politicized discourses, helping to shape shape richer spatial and territorial imaginaries.